Why would you use a Fascist salute to celebrate a football victory?

By Tea Sindbaek Andersen & Tippe Eisner

On 4 April 2019, we visited a Danish High School, with the main ambition to make Danish teenagers aged 16-19 reflect upon and interact with the ways in which we relate to genocide history. Along with us, we had a small group of students from Balkan/Eastern European Studies at the University of Copenhagen. As an important outcome of the workshops were memes, and some of them are displayed throughout this text.

What we were hoping to do during this event was, by giving them a certain knowledge, to enable the young high school students to work in an experiential way with this knowledge. Through explorative and creative group work, we were hoping to make them reflect and make a stand. Thus, we were wishing that we could confront the indifference to genocide history and, if we were truly successful, that we could perhaps also draw that reflection back to wondering about the dangers of indifference in contemporary Danish society.

The event was prepared in collaboration with two high school teachers in history, and it was their groups of students (40 students in total) we were to work with on this day. The students had received material in advance, which introduced them to the topics of genocide history in the former Yugoslavia. One of the teachers had prepared the main part of the teaching material, a very short description of 20th century Yugoslav history, as an audio file. Moreover, the teachers had prepared groups of 4-5 students, mixing them across classes and personalities.

The first element of our experiential learning event was a brief lecture that repeated and elaborated on their concise Yugoslav history with the aim to remind them of the background for some of the historical metaphors and associations that are being used in contemporary football culture in Serbia and Croatia. This was followed by an introduction to three cases of appropriation of genocide history in football culture: Firstly, that of Croatian national team captain Josip Šimunić celebrating a victory in 2013 by chanting a Fascist salute associated with the genocidal Ustasha regime. Secondly, that of the fans of Red Star Belgrade parading banners with the city name Vukovar in Cyrillic, thus reminding of war crimes during the war in Croatia. And finally that of Serbian national coach Mladen Krstajić’ reference to the war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ICTY, as an example of selective justice comparable to the use of video referencing at the 2018 world championship in football. We then asked the student groups to discuss what these uses of genocide and war crimes history were about and why anyone might want to draw on such historical references to celebrate or make particular statements in football culture.

The idea with the group work was to make the high school students spend some time reflecting on these questions. We had prepared a selection of accessible online sources for the students to consult if they wanted to explore or pursue certain aspects of the three cases further. By doing this, we were hoping to make the students immerse themselves in the questions and somehow take ownership of their own investigation as a basis of reflecting over the questions.

Yet, a main aspect of this reflection was the presence of our group of university students with a specialization in Yugoslav history, who walked around among the groups, making their knowledge and insights available and contributing to facilitating the discussions. This did seem to create open and thoughtful talks, allowing the high school students to explore issues and pose further and sometimes more fundamental questions. Indeed, this dialogue between the teenagers and the university students may have been the most fruitful experiential element of the event.

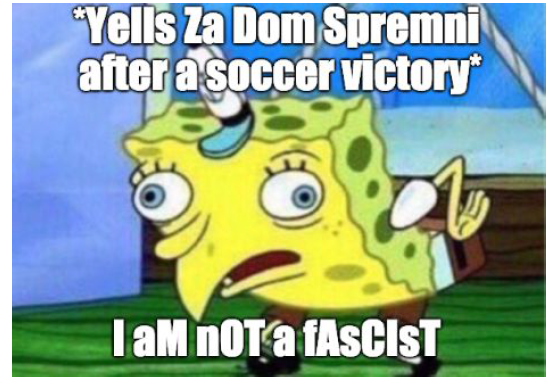

The feedback from the group discussion concentrated on the role of nationalist ideology and the ways in which it may dominate the perspective on history, to the extent that any sensitivity to historical experience and genocide history be excluded. Yet, the high school students also pointed to the ambiguity of football culture, the highly affective character of international sports, and the possible inability of sporting personalities to actually know what they are saying. We then asked the high school student groups to create some kind of ‘product’ in whichever form they would prefer – a poster, a meme, a written statement, an audio file – as their reaction to this type of use of war crimes and genocide history in football culture. By doing this, we were hoping to make them position themselves as persons and subjects, and as members of a small teenage collective, in relation to these questions.

Did we succeed? The ‘products’ were truly interesting. Some of them testified to really thoughtful discussions among the high school students. Several groups pointed out how they thought these actualizations of genocide history by football heroes could create anger and hate, resulting in deep divisions among groups in society and potential ostracism of groups and individuals. Also, some students pointed out the negative effects such uses of genocide history could have upon the relationships between different states and nations. Some groups produced ‘memes’ often based on widely recycled and remediated images from the internet and edited these images to express sophisticated and humorous condemnations of the football heroes and their uses of history. One group very neatly emphasized the use and manipulation of affect, and also the dilemma in relation to nationalist discourse between ensuring freedom of speech and keeping emotional expressions within the acceptable. Other groups stuck to simpler messages calling for mutual respect and understanding and more LOVE within the world of football, or emphasizing that we should use sport to create communities across borders. One group called for collaboration and forgiveness. And one group simply argued that “the past should be shelved!”

Thus, the experiences of researching and discussing these issues and actually producing a lasting statement about them seem to have pushed some thinking among our high school students. There is certainly an awareness of the problem, and also some quite sensitive reflections about the risks connected to irresponsible and disrespectful uses of genocide history.

Did we manage to return the reflections to considering the problem of indifference in Denmark? Probably not. Indeed, one high school student asked as a concluding remark if anything like the wars of the 1990s, the campaigns of ethnic cleansing and genocide could ever happen again in Yugoslavia, and he and his fellow students looked highly skeptical at the suggestion that this kind of thing could happen anywhere – even in Denmark. A few of them actually looked a bit frightened at the thought of this possibility.

Afterwards, we received feedback from the two high school teachers, who had participated in the event with their students. They informed us that the students had been very satisfied and enthusiastic about the event – in particular working with the subject in a different style than usual class-room teaching, and they felt that they had gained a lot of (new) knowledge. So perhaps in the longer term, more reflections will pop up.